If you have ever ground your own coffee, then you’ve probably tried the Weiss Distribution Technique (WDT). Possibly even without realising you were doing something that had a name, you might have grabbed a paper clip and done a little puck raking just for the pure catharsis of breaking up those clumps of coffee grounds. But have you ever tried doing WDT in wet coffee? We hadn’t — not until we interviewed Dan Shusett last month. Dan is the creator of the Tricolate coffee maker, which has been garnering a lot of attention from baristas over the last couple of years.

If you’re curious to learn about the history and efficacy of the WDT, here’s a piece we published about it last year entitled Should we all be Doing WDT Again? The short answer to that question is: yes you should be — if you have the time. The method is named for John Weiss, who developed the technique back in 2005 as a way to compensate for grinders, especially smaller home grinders, that produced excessive clumps. But the question we pose in this blog post is, should we all be doing Wet Weiss distribution? This week our Dean of Studies, Jem Challender, teamed up with barista Lloyd Meadows, the founder of Tortoise Espresso, to find out the answer to that question. And the short answer is again: yes you should be!

The Tricolate belongs to a category of coffee makers referred to as zero-bypass brewers, meaning, all the water in the brew goes through the coffee bed. That concept in itself is not brand new as any lover of Vietnamese Phin cà phê will attest to. However, the Tricolate, and, more recently, the Nextlevel brewer, are two examples of a new generation of precision brewers designed to house filter papers in a way that facilitates high extraction yields and great flavour clarity together with fine filtration.

If you’re considering going down the zero-bypass rabbit hole — something we highly recommend you do — there are a few things you need to know: Zero-bypass brews take longer to draw down than V-shaped cones; sometimes much much longer. The Tricolate comes with a dispersion screen which is absolutely essential. If you pour onto the coffee bed of a Tricolate without the dispersion screen in place, or if you attempt something like NSEW distribution (stirring) during blooming, your brew will most likely take in excess of 15 minutes to draw down. Any kind of heavy agitation simply chokes up your brew. As you can see in the video clip in this lesson for the Percolation course, goose necked pouring kettles fluidise a coffee bed, which certainly seems to work nicely for V-shaped pour-overs but it seems like a definite no-no for zero-bypass brewers.

Gentle agitation is advised by almost everyone who has tested this coffee brewer. But there’s one problem with the gentle approach. If you zoom in on literally every instructional video about the Tricolate on the web, you will notice quite an obvious ring of trapped air bubbles around the sides of the coffee bed. If you’ve ground a little too coarsely on the Tricolate, these air bubbles erupt to the surface and disturb the nice level coffee bed you’ve taken pains to create with your careful gentle blooming and swirling. We took this problem to Dan Shusett and he introduced us to the notion of Wet Weiss distribution.

Putting Wet Weiss to the Test

In this test we used the popular Scott Rao method for the Tricolate, with a nice Colombian Caturra roasted by Code Black. We made ten separate brews, half using the ordinary Rao method as a control method, and half using the Rao method with the addition of Wet Weiss. We used the new BH Comb for the Weiss Distribution with seven pins configured like this.

The BH comb allows for many different configurations of pins to allow for different WDT techniques. This image shows our preferred configuration, with 7 pins.

The BH comb allows for many different configurations of pins to allow for different WDT techniques. This image shows our preferred configuration, with 7 pins.

For the Wet Weiss distribution, we exactly replicated the first set of brews: we added the bloom water, swirled gently, and then simply performed one full rotation around the outer edge of the coffee bed and one circle around the inside, another swirl — that’s it.

We tasted each of the final brews, and measured the TDS with a refractometer.

Results

The Wet Weiss technique was evidently highly effective at removing the apparent layer of trapped gases. The coffee bed was visibly darker and no bubbles were visible within the bed of coffee. Once the brews started, there were no issues with bubbles rising to the surface.

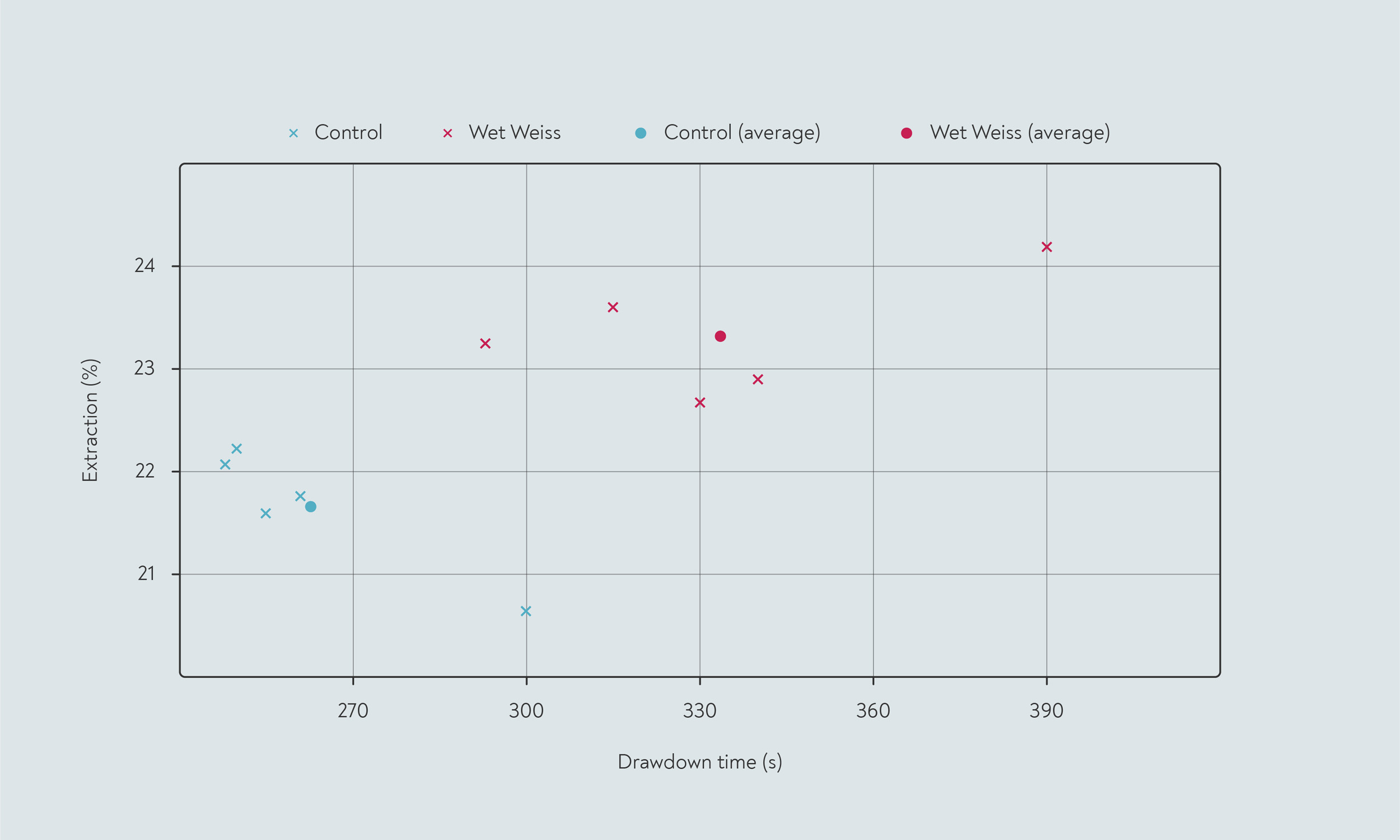

The Wet Weiss method also dramatically increased extraction. The extraction yields in our brews averaged 23.33% for the Wet Weiss compared to 21.66% for the control method.

What was also encouraging was that using the Wet Weiss method didn’t massively increase the contact time like normal NSEW stirring had been doing for us. Contact times were, unsurprisingly, longer with Wet Weiss: 5:34 minutes on average compared to 4:23 for the control method.

| Control | Wet Weiss distribution | |||

| Drawdown time (s) | Extraction (%) | Drawdown time (s) | Extraction (%) | |

| 300 | 20.64 | 293 | 23.26 | |

| 248 | 22.08 | 315 | 23.61 | |

| 261 | 21.77 | 340 | 22.91 | |

| 255 | 21.6 | 390 | 24.2 | |

| 250 | 22.23 | 330 | 22.68 | |

| Average | 263 | 21.66 | 334 | 23.33 |

A T-test confirmed that the differences for both contact time and extraction yield were statistically highly significant (p<0.01).

The Wet Weiss method also seemed to improve the flavour of the brews. Lloyd Meadows compared the flavours of both sets of brews, and noted that ‘[the Wet Weiss brews possessed] more sweetness, more depth of flavour and a cleaner finish.’

Contact Time

In most brewing methods, contact time is linked to extraction — so any method that increases contact time can be expected to increase extraction by a certain amount. We’ve seen this effect in our experiments on stirring the bloom in a V60. In those experiments, stirring the bloom increased contact time by about 10 seconds, and increased extraction by about half a percentage point.

Plotting our results from this experiment on a graph shows the relationship between extraction and contact time in these experiments more clearly:

While any agitation method could be expected to increase both drawdown time and extraction, even those Wet Weiss brews that had a similar drawdown time to control brews still had a much higher extraction. In fact, the control brew with the longest drawdown time also had the lowest extraction, perhaps indicating clogging and channeling in this brew. This suggests that Wet Weiss is increasing extraction by more than just increasing the contact time.

Wet Weiss has some other clear advantages over other methods of agitation. Stirring in the Tricolate causes too much clogging to be practical. When we tried to use a gentle stirring method with the Tricolate, we ended up with drawdown times of around 15–20 minutes — by comparison, the increase in drawdown with Wet Weiss is very modest.

Swirling, on the other hand, is not effective at getting rid of all of the bubbles in the coffee bed. No amount of spinning the bed completely gets rid of the trapped gases, and excessive swirling can also cause the Tricolate to choke.

Contact time is quite an interesting parameter when it comes to the Tricolate, because even though it is a pour-over method, brews that take as long as 10 minutes to draw down can still taste surprisingly vibrant. That’s certainly not something we would say about a V-shaped pour-over that took 10 minutes to draw down.

Based on this experiment, we would encourage anyone to try Wet Weiss when developing a new Tricolate recipe. After finishing this experiment, of course we then started to wonder, if we should be doing Wet Weiss Distribution in our V-shaped pour-overs too? And the answer to that is yet to be determined…

0 Comments