Every once in a while, a single cup of coffee comes along that redefines your idea of what coffee can taste like. When that happens to us at BH, it sends us down a rabbit hole: We have to find out what made the coffee taste that way, and what we can learn from the way that particular coffee was made.

Our Dean of Studies, Jem Challender, tasted one such cup recently at Tortoise Espresso in Castlemaine — a coffee from Behind The Leaf in Myanmar, roasted by Toby’s Estate. ‘It was completely balanced. Bubble gum — the producers mention “coconut sticky rice” and for sure that was there in abundance, and even a thirst-quenching nashi-pear finish,’ Jem says. ‘And it made a cappuccino to rival the winner of any barista competition that I’ve ever been involved in’.

We asked Charlotte Malaval, green buyer for Toby’s Estate, what made this coffee stand out to her. ‘Coffee from Myanmar really has a unique profile, with this consistent cherry-anise combo, with unbelievable depth, mouthfeel and overall structure,’ she says. ‘Since [Behind The Leaf founder] Melanie started experimenting more with fermentation, she is pushing it to more confectionary profiles, and tropical fruits. It is still very clean and measured, which is why I love them so much.’

Coffee and banana plantations in northern Myanmar

Coffee and banana plantations in northern Myanmar

This lot was processed as an anaerobic natural, with the whole cherries fermented in sealed tanks for 72h before being dried. What makes the method distinct is the unusual starter culture they used to kick-start the fermentation: a yeast cake designed for use in making rice wine. These yeast cakes are widely used throughout southeast Asia, and often referred to by their Chinese name Qū.

‘These “yeast balls” have been cultivated for thousands of years, starting in China,’ says Behind The Leaf founder Melanie Edwards. ‘The beauty is they are all different, but their purpose is one and the same — making an alcoholic beverage. But now in the “specialty” world of rice wine making and coffee making, we have learned that the fermentation and starters used can also aid in fragrance and flavour.’

Traditional yeast cake starters, used to make rice wine

Traditional yeast cake starters, used to make rice wine

The yeast cakes are traditionally based on a spontaneous fermentation (like a sourdough bread starter) using rice or wheat, which is then dried to create a concentrated cake of wild yeast, fungi, and bacteria. The process is not unlike the koji-based process used to make Finnish Barista Champion Kaapo Paavolainen’s coffee for the World Barista Championships last year, but using a wild mixture of organisms rather than a single commercially cultured yeast.

During drying, the cherries formed a whitish powdery layer on their skins, indicating extensive colonisation by one or more strains of fungus in the starter. This layer seemed to protect the cherries against other moulds: on wet days, naturally-processed coffees would be affected by a green mould, while the cherries fermented with the yeast cake stayed white.

Coffee cherries covered with a white powdery layer after fermentation with yeast cake starter

Coffee cherries covered with a white powdery layer after fermentation with yeast cake starter

Using one fungus to prevent the growth of another is a well-known strategy in microbiology, and is widely used in the wine industry, for example (Suzzi et al 1995). The fungi compete for space and nutrients, and some even secrete chemicals that prevent other fungi from growing. “Almost all saccharomyces yeast strains are biological protectors against spoilage organisms like moulds,” explains coffee processing specialist Lucia Solis. “Even your common bread starter yeast you can buy in a grocery store will have this effect on spoilage organisms.”

Wild Fermentations

Since the yeast cakes the producers used are based on spontaneous fermentation, it’s impossible to know exactly which species of yeasts and bacteria they contained. ‘The starters are all secret recipes and include mixed cultures that are complex and have a symbiotic interaction,’ says Melanie. ‘There are moulds, yeasts and bacteria present as well as their metabolites.’

Similar starter cultures have been studied in nearby countries and found to be highly variable. In China, wheat-based starters are dominated by various Aspergillus fungi, especially the koji fungus A. oryzae (Ji et al 2018). In Thailand, however, the yeast Saccharomycopsis fibuligera is more common (Limtong et al 2002) while in Vietnam researchers found several different yeasts including Rhizopus oryzae, and a wide range of lactic acid bacteria (Tanh et al 2008).

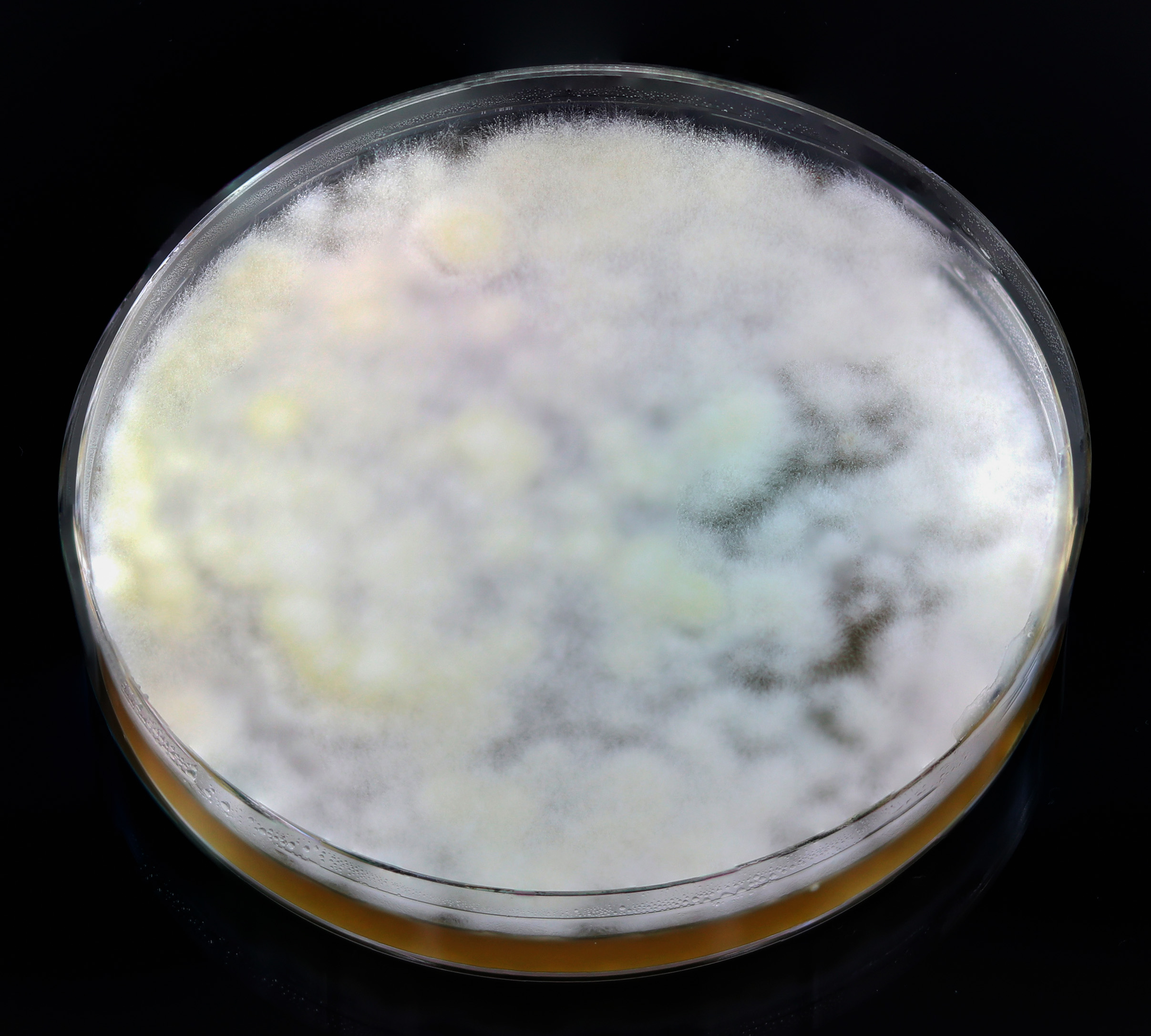

Aspergillus oryzae, the koji fungus used in Japan to make sake, miso, and soy sauce.

Aspergillus oryzae, the koji fungus used in Japan to make sake, miso, and soy sauce.

While the species found in yeast cakes are mainly adapted to growing on starchy foods like rice, many of them are found in coffee fermentations as well. Some strains of S. fibuligera are very efficient at breaking down the pectins in coffee mucilage (Haile and Kang 2019), while strains of Rhizopus oryzae found in green coffee were shown to prevent the growth of ochratoxin-producing fungi (de Almeida et al 2019).

‘Melanie is getting to understand the microbes and microorganisms that she has around, by getting them tested and analysed, so we are learning more and more,’ Malaval says. It’s not always possible to get the same result every time, though. ‘Other variables are also changing, such as the fermentation time, which village the cherries come from, the mix of varieties.’

Even if you know which species are present, it’s hard to predict which ones will take part in the fermentation, Lucia explains. ‘With a spontaneous starter, you have a mixture of around one million microbes and you never know which will dominate. So while you can have better results in the cup from spontaneous starters, you will not get consistency. How valuable is a great cup profile that can not be replicated?’

‘Of course it is more risky what we are doing,’ agrees Melanie. ‘I have begun to experiment with Aspergillus oryzae (Koji), but I have not tried any commercial strains of yeast.’ Instead, she is seeking consistency by making her own version of the yeast cake starter, and is looking for help with identifying the microbes involved.

The good news is that the samples from this year’s harvest are coming in already and are tasting delicious, Malaval says, so Toby’s Estate are planning to buy more of the yeast cake fermented coffees this year.

The Importance of Drying

The producers at Behind The Leaf noticed one other thing about the cherries in this process: the husk dried out more quickly than the standard naturally-processed cherries, although the overall drying time for the seeds was the same. This faster drying may alter the balance between the different species that take part in the fermentation. This is the same effect that we speculate made it possible for Nikolai Fürst to achieve 500-hour fermentations in Colombia.

There is one other prominent example of fruit becoming dehydrated after colonisation by a fungus: Botrytis cinerea in wine grapes, also known as “noble rot”, which, like S. fibuligera in coffee, breaks down the pectins in the fruit. Under the right conditions, this causes grapes to lose moisture and shrivel up, making the juice from the grapes become more concentrated and intense. The juice from these grapes can be used to make highly prized dessert wines such as Sauternes or Tokaji. Grapes affected by botrytis are often also colonised by acetic acid bacteria, which produce acetic acid and ethyl acetate (Nigam 2014), two compounds that can contribute to fruity flavours in coffee. It’s possible that the fungus from the yeast cakes causes the coffee cherries to dry faster in a similar way, although how this affects the final flavour of the coffee remains to be determined.

Specialty Coffee in Myanmar

Coffee has been grown in Myanmar since the late nineteenth century, but for most of that time the majority has been low-quality coffee, produced for the local market or shipped across the border to neighbouring countries, where it was sold well below the market price. The specialty industry was virtually non-existent until 2014, when a USAID-backed project was set up to help producers get access to better equipment and techniques and reach new markets.

Coffee cherries being dried in the sun. Equipment for wet milling is rare in Myanmar, and most coffee from the country is naturally processed.

Coffee cherries being dried in the sun. Equipment for wet milling is rare in Myanmar, and most coffee from the country is naturally processed.

Myanmar has the potential to produce large amounts of high quality arabica, though. The highlands in the north of the country boast good soils, plenty of rain but a distinct dry season for drying coffee, and elevations above 1,000m (Basu et al 2019). The overall production quality is improving, and in recent years a small but rapidly growing number of farmers are wholeheartedly embracing specialty coffee, and producing some outstanding lots. ‘We really do have ideal weather for processing clean naturals,’ says Melanie. ‘We get occasional rain during harvest, but this year was perfect weather for fermentation and drying.’

Myanmar’s coffee farms have a lot of potential for high quality coffee production.

Myanmar’s coffee farms have a lot of potential for high quality coffee production.

The unstable political situation in the country has limited investment and threatens producers’ access to international markets. After the military coup in 2021, the producers at Behind The Leaf had to pursue their fermentation experiments without the help of outside consultants, and had to go to extraordinary lengths just to be able to ship samples out of the country, they explain in an interview for Toby’s Estate.

Considering these challenges, getting the opportunity to taste this coffee was an enormous privilege. Our hope is that as more extraordinary coffees like this make it out of Myanmar, it will raise the profile of this little-known origin within the specialty industry, and help more growers get access to better prices for their coffee.

0 Comments