Coffee prices have increased dramatically this year, after years of historic lows. In June 2020 the ‘C’ price, the benchmark price for coffee, sat below $1 per lb. In July of this year it reached more than $2, and may yet increase further. After struggling with low prices for so long, this price increase should be good news for coffee growers — and yet, many will not benefit at all.

For one thing, the price rises were precipitated by a bad year for coffee production, mainly caused by adverse weather in coffee-producing countries, including droughts in Brazil earlier this year. International trade has also been hit by a global shortage of shipping containers, and the ongoing effects of the coronavirus pandemic (ICO 2021). Finally, coffee trees were hit by severe frosts in Brazil this year, which is likely to affect production for years to come.

Coffee trees damaged by frost in Minas Gerais, Brazil. A severe frost in Brazil can impact coffee prices for several years as trees may take several seasons to recover, and seedlings will tend to perish. Losses for the 2022 crop are estimated at 4.5 million bags, according to Exportadora de Cafe Guaxupe Ltda, an green coffee exporting company based in Minas Gerais. (Batista and Perez 2021)

Coffee trees damaged by frost in Minas Gerais, Brazil. A severe frost in Brazil can impact coffee prices for several years as trees may take several seasons to recover, and seedlings will tend to perish. Losses for the 2022 crop are estimated at 4.5 million bags, according to Exportadora de Cafe Guaxupe Ltda, an green coffee exporting company based in Minas Gerais. (Batista and Perez 2021)

Even for producers who aren’t facing low yields this year, many will have sold their coffee long before it was harvested, when prices were still very low, so can’t benefit from the recent recovery in the C price. This week, Reuters reported that some farmers in Colombia are breaking contracts and holding back as many as 1 million bags of coffee — 10% of the total crop (Angel 2021). After prices jumped by 55% this year, it has become more profitable for many growers to default on their contracts and suffer the consequences, in order to sell their coffee elsewhere at the current market price.

An Unequal Market

Many different approaches have been proposed to address the inequality and volatility inherent in the coffee trade, but so far none has led to wide-scale changes in the market. So what can consumers do to ensure their money is being distributed as fairly as possible?

The parallels of the recent shifts in the coffee market with previous price shocks are clear, explains coffee historian Jonathan Morris in an article for The Conversation. The history of coffee is characterised by a cycle of low prices when harvests are good, followed by price spikes only when some disaster hits coffee production, such as the devastating frosts of 1975 in Brazil, or the more recent leaf rust epidemics in South and Central America, Morris explains.

“The bitter irony of the coffee market is that prices for producers only improve when many of them suffer unsustainable losses.”

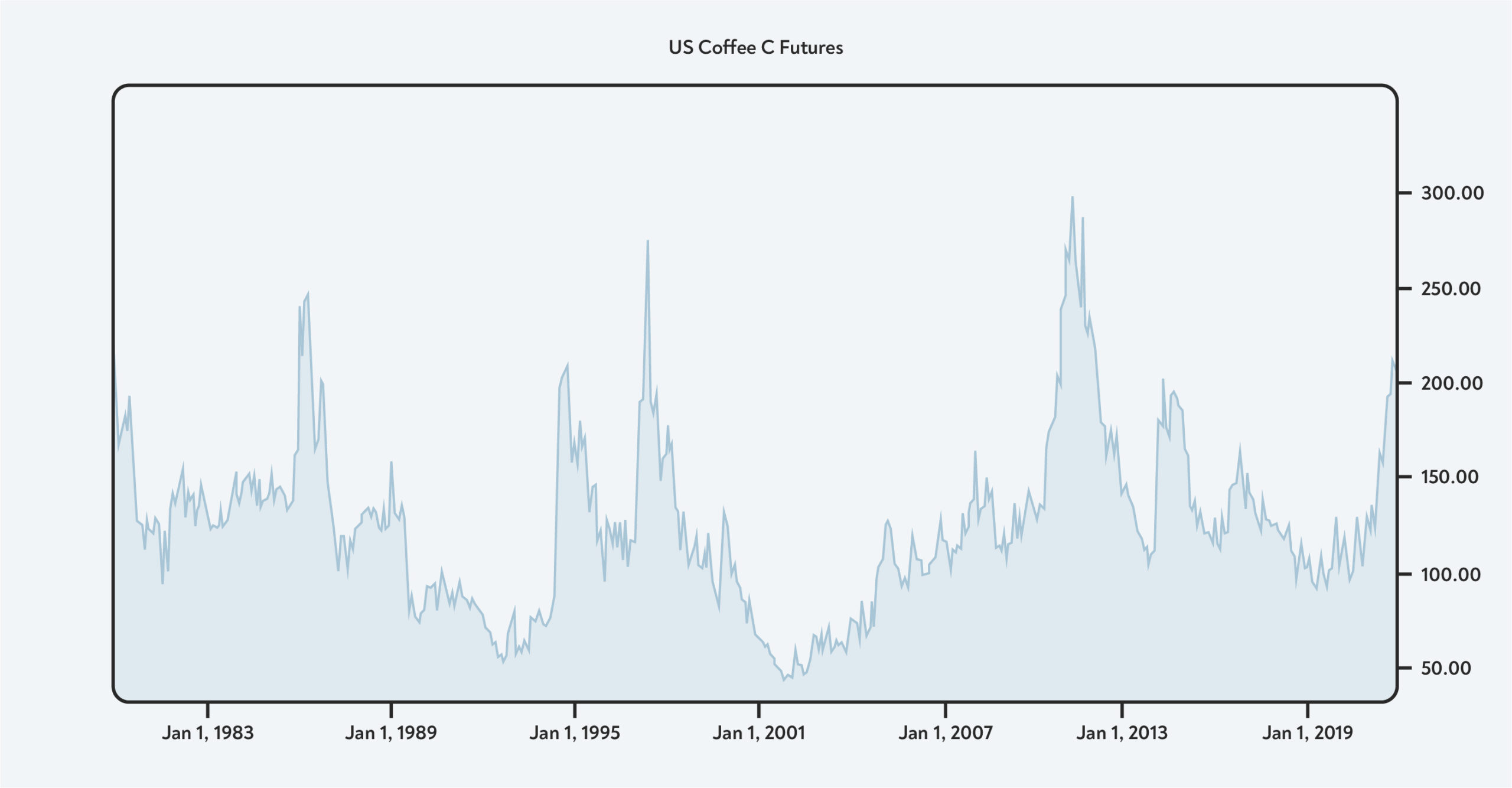

The coffee futures market (called ‘C’) is used to set coffee prices around the world. Price rises usually occur only in response to a disaster affecting coffee production, such as the spike in prices during the 2008-13 leaf rust epidemic. Source: Investing.com

The coffee futures market (called ‘C’) is used to set coffee prices around the world. Price rises usually occur only in response to a disaster affecting coffee production, such as the spike in prices during the 2008-13 leaf rust epidemic. Source: Investing.com

The low prices paid for coffee mean that less than 10% of the value of the US$200 billion coffee industry remains in producing countries (Miatton and Amado, 2021) — a symptom of an unfair and unequal trade that has persisted for centuries. In some ways, the solution is simple: farmers need to be paid more for their coffee, whether the market is high or low. And yet, organisations such as Fair Trade that attempt to address the imbalance in this way have had limited success. In this paper, Colleen E. Haight argues that they may even hurt smallholder farmers in the long term.

Transparency and Direct Trade

More recent approaches to the problems with volatile coffee prices involve a focus on transparency — providing information about what prices are paid all along the value chain, so that consumers and coffee buyers can make informed decisions about where their money is going.

“We are painfully aware that 40 years of Fair Trade has not done enough to counter the incredible power imbalances in international trade. We are passionate about economic justice and believe that transparency is key in achieving this,”

says Robin Roth, CEO of Traidcraft, in a statement supporting the Transparency Coffee Pledge.

This approach, along with related approaches like the Specialty Coffee Transaction Guide, and blockchain-based transparency initiatives like Farmer Connect, aim to shift the balance in the value chain in the producer’s favour, by making it clear how much a farmer is paid for their work, thereby encouraging and rewarding fairer payments. Paying above the C price for specialty coffee can help to protect farmers from the worst of the price shocks (Cadena 2019) — but is not enough by itself, however. To truly make a difference, coffee buyers would need to pay more than the market value for coffee of that specific quality, benchmarking the price against equivalent coffees, rather than against the C price.

Trying to pay above ‘market value’ for a particular coffee comes with problems of its own, such as deciding how the additional funds should be distributed. A common approach is to use the money to support development projects in the coffee’s country of origin, but this can be — often rightly — criticised as a marketing tool, rather than a genuine attempt to rectify the imbalance in the coffee trade.

A different tactic comes from companies that try to bring more of the value chain into producing countries. This can include the various forms of so-called ‘Direct Trade’, where a coffee producer negotiates a sale directly with a coffee roaster in a consuming country. Depending on how the coffee is sold, this might bypass a multinational exporting or importing company — potentially keeping more of the value of that coffee in the country of origin.

Coffee sacks waiting to be shipped from a warehouse in Brazil. The role of exporters is much more complex than simply being a ‘middleman’ and can involve everything from working with farmers to maintain quality, looking after dry milling, and financing future harvests

Coffee sacks waiting to be shipped from a warehouse in Brazil. The role of exporters is much more complex than simply being a ‘middleman’ and can involve everything from working with farmers to maintain quality, looking after dry milling, and financing future harvests

To try to understand these issues better, this week we spoke to a green coffee trader whose experience traverses commodity and specialty markets. We interviewed Mette-Marie Hansen, Managing Director of Kenyacof, the Kenyan subsidiary of Swiss-based multinational Sucafina. Mette-Marie has previously worked as a green buyer for specialty coffee roasters Java in Oslo, Ritual Coffee Roasters in San Francisco, as well as 49th Parallel in Vancouver. (We interviewed Mette-Marie last year on the subject of fermentation in Kenyan specialty coffee.)

She feels that the contribution of the coffee exporters and traders to the imbalance in the coffee trade is frequently overstated. Exporters are sometimes considered ‘middlemen’, taking a cut of the profit without adding any value, but their profit margins are frequently overestimated.

“I would love there to be more transparency,” she says, “because then it would be clearer to everyone that we often get just 1-2% of the FOB price — our margins are super slim.”

Direct trade is rarely as simple as roasters present it, Hansen adds, and still requires the services of importers or exporters.

“If direct trade worked like people say it does, I would just be putting coffee in bags and putting labels on them, but in reality we do much more to add value for both the grower and the overseas buyer.”

Roasting at Origin

A more direct-action is offered by companies that have set up roasting operations into the country of origin, exemplified by companies such as Moyee and Amor Perfecto. A coffee roaster that includes both wholesale and retail operations can be one of the most profitable parts of the value chain, with profit margins of nearly 12%, once all costs have been accounted for (SCA 2017). Bringing this part of the business into the producing country can create jobs and provide much-needed foreign currency for the economy — a particular problem in Ethiopia, for example (Amboko 2018).

As well as contributing to the local economy, creating jobs in producing countries in this way is valuable in its own right, Hansen says.

“In Kenya, and across Africa, the majority of the population is young, and there are no jobs for them. People in Kenya have an education, but there is no job creation.”

Creating jobs locally can also give people valuable new skills such as roasting or cupping coffee, she adds.

“Why shouldn’t coffee be roasted at origin where labour is cheaper and you can create jobs? I personally believe job creation is the future of Africa, where 75% of the population is young and unemployment, one of our biggest problems.”

When the jobs are controlled by a western-owned company, however, it raises the question of whether they are simply taking advantage of that cheaper labour.

“If you pay someone to roast coffee in Nairobi rather than Berlin for example, I’m guessing you’re not going to pay them the same — but if the coffee is being sold at the same price, where does that margin go?,” she asks. “I think you would need to know if they sell the coffee at the same price as their competitors in the destination market, and if so, is that profitability trickling back to the workers, do they pay more to the farmers?”

In the case of Moyee for example, they approach this by being transparent about their payments to farmers, and the other projects they undertake to share more value with the producing countries. They also benchmark their workers’ salaries by the International Wealth Index.

Providing transparency is complicated, however, and listing the payments made doesn’t always tell the full story.

“Transparency reports mention terms like ‘farmgate price’ and the ‘FOB price’ — but even those definitions can be fairly loose,” Hansen explains. “It is hard to benchmark [prices], because the value chain operates so differently in different countries.”

Just listing the price paid misses some information, such as who is being paid and what costs are involved, she explains.

“The interesting thing to talk about is what everyone’s margins are,” she says — “but even comparing this margin to the cost of production doesn’t guarantee a good living for everyone in the value chain.”

“Farmers in Kenya generally have a 60-70% profit margin — which is huge. But the total payment is very small, because they have very little coffee,” she says. “It’s not enough for them to have a good life, because they own very little land and produce very little volume.”

A coffee farm in Kenya. Kenyan beans fetch relatively high prices, but the typical income for farmers in the country is still low due to poor yields and small farm sizes

A coffee farm in Kenya. Kenyan beans fetch relatively high prices, but the typical income for farmers in the country is still low due to poor yields and small farm sizes

Futureproofing the Value Chain

We asked Mette-Marie Hansen how a consumer or coffee buyer can ensure that their money has the maximum impact in the producing country.

“That’s a very difficult question,” Hansen says. “If the grower name or farm name is on the bag then at least the coffee has some sort of identity, and you would assume that if someone reveals the identity of the supplier, then everything is in order in the value chain … I don’t know what the future is, but I expect technology has something to do with it. There are some really good initiatives like Farmer Connect, a transparency platform. You get a QR code on the bag, you can scan it and see the whole supply chain.”

This type of initiative helps to promote specialty coffee, because the consumer can see the impact that the money they spend has, she adds. However, it’s not clear who will carry the costs of developing this type of software and recording the information, Hansen says. “I don’t feel many roasters are willing to contribute to develop this kind of transparency tool.”

Ultimately, technologies like blockchain that record and secure transactions throughout the value chain might totally change the way coffee is traded, Hansen suspects.

“Our biggest competition soon [as an exporter] is going to be all these tech companies.”

This has already begun to affect the way other commodities are sold, she says, but it may take a bit longer before it has a big effect in the coffee industry.

“Selling coffee is a little bit more complicated than selling apples, after all.”

Until that technology becomes more common, then, existing transparency initiatives are the best way for coffee buyers to check if fair prices are paid all along the value chain. As buyers’ interest in this area grows, our hope at BH is that the industry will develop better transparency tools and stronger benchmarks for fair prices tailored to each producing country, to allow coffee farmers to fully benefit.

Great catch Andre, indeed Speciality Coffee is the best from 2 to 7 weeks after roasting. We do aim to get our coffee by then at your door. Important is here to also look at the green bean time between the farmer and roaster. Because we roast in origin, this is ultra-short. Green beans of other coffee roasters and traders spend months going from the farm to Europe, which decreases the quality. An example of this you see on the image above of the coffee sacks in the warehouse in Brazil. Our coffee wins blind taste tests even months after roasting.

If lucky the coffee is from a direct trade company that really cares about the farmer, but that actually says little about the impact. Most of the time the company pays the farmer something extra but you really need extensive research to find out if that is actually enough. We give the farmer 6-7 euros per kilo and record this on the blockchain to ensure transparency. We also have tree-planting projects where we extend the yield of the farmers. By doing this we are getting the farmers toward a living income.

In the last 3 years, we spend 400.000 euros on our farmers to increase yield and quality. But we are not there yet. We call ourselves the least unfair coffee company 🙂 We are not here to sell coffee, but we are here to set up the business model of the future. And yes that brings us great coffee for you because the chain can’t be shorter (there even is no direct trader). That is even better for you because we can bring you specialty coffee for a better price than anyone else. So the choice for Moyee is to contribute to the business model on the future with every sip, where the whole chain is equally divided. Everyone wins in this FainChain model.

Best, Gijs

Hi Andre, Gijs, thank you both for commenting.

Yes, handling freshness in this scenario is a complex challenge and one that would deserve its own article. There are plenty of ways that could be used to increase the life of roasted beans – for example nitrogen flushing. There is also definitely something to be said for the advantage of roasting the green coffee while it is fresh – take a look at https://web.archive.org/web/20170909032829/http://www.jimseven.com/2016/08/09/a-challenging-idea-about-fresh-coffee/ for an interesting discussion around this.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that the market for not-especially-fresh supermarket coffee, far from being niche, is much larger than for super-fresh locally-roasted specialty coffee. Taking a slice of that pie back to origin could have an even bigger impact. For the specialty side, it’s not likely that roasting at origin will completely replace local roasters, for reasons of freshness and logistics. If I understand correctly, even Moyee roast some of their coffee in the Netherlands for this reason.

For a few weeks I got a lot of targeted ads from Moyee on my social media, thought it was a good concept but immediately thought of the obvious problem of freshness (which isn’t touched on in this article unfortunately).

A quick search (just as a quick example) tells me sea freight from Kenya to the UK takes 34 days. Even it it’s one day from roasting to shipping (it isn’t) and Moyee lives in whatever UK harbour (they don’t) and stock nothing and ship everything same day (they don’t) and we receive it same day (we don’t) that’s still already 5 weeks. In terms of freshness/quality how is it any better for the customer than supermarket shelf coffee?

Realistically it’ll be a pretty niche market if a brand’s selling point is “no fresher than anybody else on this shelf, more expensive but we’re helping Kenya”.