After approximately 10 minutes of contact with water, coffee grinds lose their buoyancy and sink to the bottom of a brewing vessel. Thanks to this tendency, brew methods such as the ibrik and cuppings don’t traditionally require any filtration because gravity helps to remove the grinds from the brewed coffee. Other brew methods, such as the French press, traditionally use a woven steel mesh to filter out large grind particles to make the job of decanting the brewed coffee easier. The aperture in the mesh of French press filters is usually so large, however, that it permits a large amount of coffee particles to slip through it.

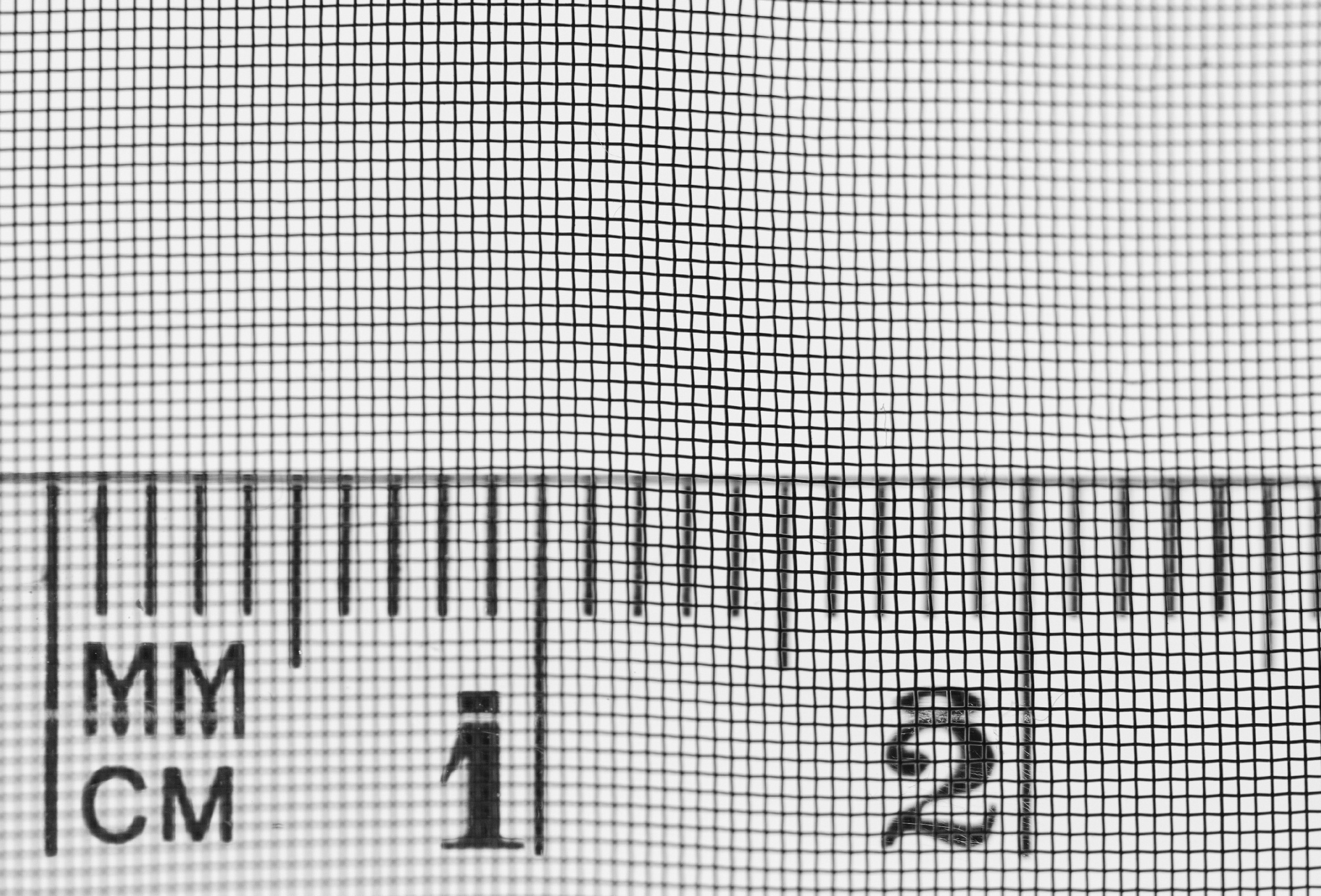

Picture: A French press filter on a ruler

Picture: A French press filter on a ruler

Filtration Criteria

When it comes to deciding how you are going to filter your immersion brews, you need to consider several criteria:

- Retention rate What particles sizes will it filter out?

- Flow rate What is the pore size, and how prone to blockages are the pores?

- Absorption level Will material stick to the surface of the filter?

- Chemical stability Will the filter material degrade? Is it resistant to an acidic environment such as a coffee slurry?

- Tensile strength Will the filter warp out of shape, affecting its ability to retain particles?

- Reusability/expense What is the environmental impact of using the filter? What is its monetary cost?

- Cleanability Will the filter impart odours or tastes to the next brew? Is the material from which it is made resistant to microbial growth?

In this lesson we’ll explore the costs and benefits of paper, metal, and fabric filters. For an in depth analysis of filtration media, this excellent post by Dr Jonathan Gagne compares the pore sizes and predicted flow rates of paper, fabric, and metal filters.

Metal Filtration

Filters made from steel come in woven gauze as well as in perforated sheets.