As is true for much of South and Central America, the vast majority of coffee grown in Guatemala is made up of ‘traditional’ varieties: Bourbon and Typica and various varieties derived from them, such as Caturra, Mundo Novo, Catuaí, Pache, Villa Sarchí, Pacas, and Maragogipe.

This reliance on two ‘parent’ varieties means that the genetic diversity is very low, which puts Guatemalan farmers’ crops at risk from pests and diseases, especially leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix). Guatemala was especially hard-hit by leaf rust in 2012, when as much as 20% of production was lost (USDA 2019). In recent decades, modern varieties with improved qualities such as rust resistance and higher yields have been trialled in Guatemala with promising results, and these varieties now make up nearly 30% of total production.

However, most farmers have limited access to government support and information about new varieties, and many can’t afford the financial investment required to plant them. Modern rust-tolerant seedlings cost US$8,000 per hectare (US$3,237 per acre) to plant, compared with US$5,000 per hectare (US$2,023 per acre) for traditional varieties. New trees don’t begin to produce a crop until at least 2 years after planting. Furthermore, resistant hybrids are generally believed to produce lower cup quality, and some that were planted at lower altitudes in Guatemala are not showing the expected disease resistance (USDA 2019).

The costs and risks involved mean that many farmers continue to rely on older, less-productive trees rather than plant new varieties. One project in Guatemala found that farms in areas with a long history of coffee production had coffee trees that were 40 to 60 years old (Technoserve 2017), even though coffee trees are generally most productive when they are fewer than 20 years old (National Coffee Association 2020).

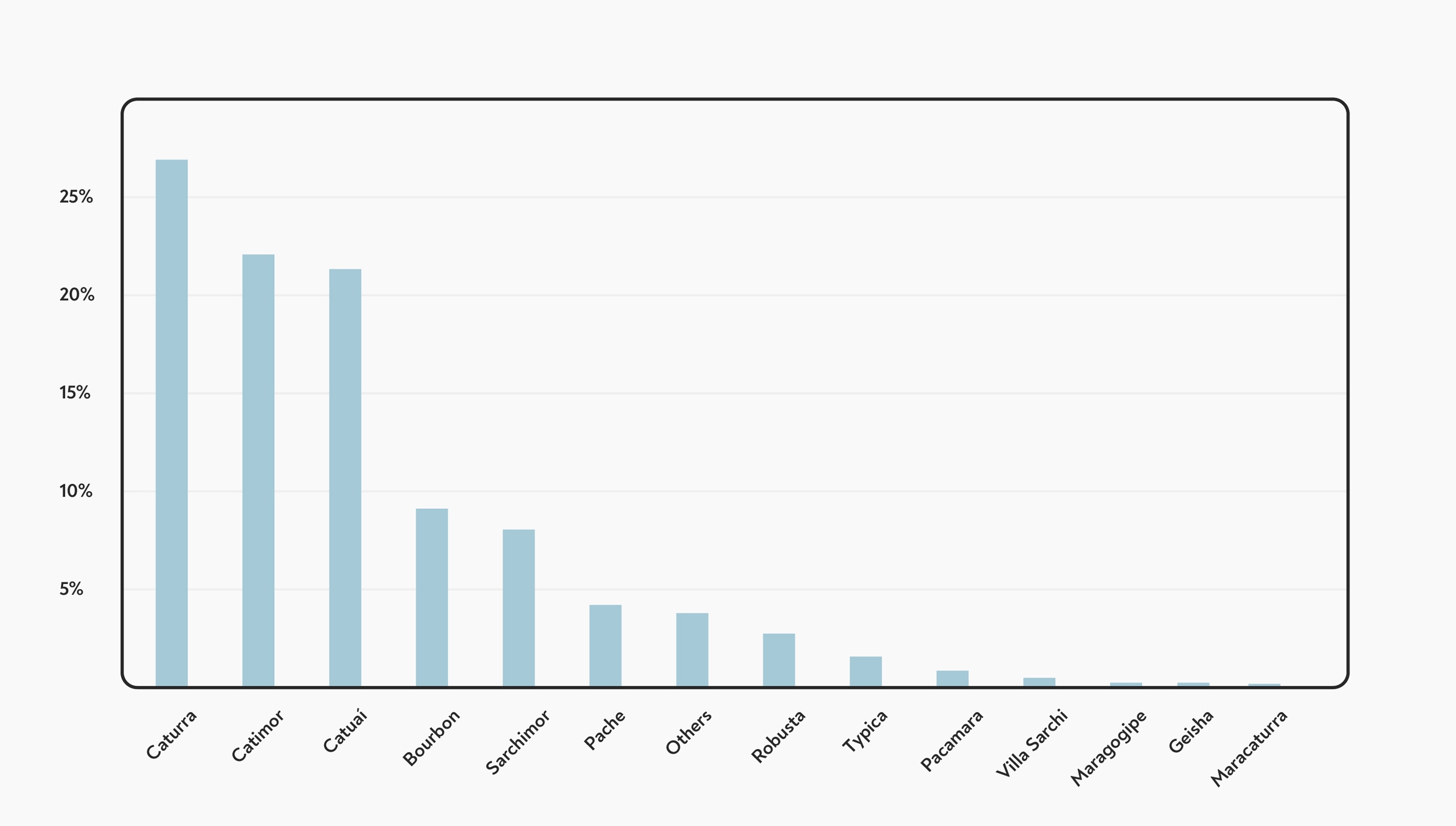

Coffee varieties grown in Guatemala in 2018,

Coffee varieties grown in Guatemala in 2018,