If you ever hang out backstage at the World Brewers Cup Competition, you’re very likely to see baristas hunched over trays of coffee, obsessively picking over their beans. Any slight blemish or discoloration, any deviation in size or shape, and the offending bean is plucked out and discarded, until only the most perfect physical specimens are left to face the judges.

Considering the high quality of coffee used in competition, most of the rejected coffee is perfectly fine to drink — but baristas know that sometimes it only takes one bad bean to ruin a cup. Armed with more uniform coffee, they can also expect a more consistent result.

A coffee has already been sorted many times by the time it reaches the barista’s hands. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that the process of creating specialty coffee هذا sorting. Cherries are sorted for ripeness when they are picked, and again in the floatation tank. The green beans are sorted by density in the washing channels, and again at the dry mill. Along the way, at every step, any defective beans are picked out, both by hand and by machine.

Sorting green coffee by hand and by machine

Sorting the coffee after roasting, on the other hand, used to be confined mainly to coffee competitions. Roasters might pick the occasional burned bean out of the cooling tray, but sorting an entire batch was too labour intensive for most businesses. All that has changed, however, as the sophisticated machines used to sort coffee beans have become cheaper, and have become more accessible to smaller, specialty coffee roasteries.

Perhaps the first specialty roastery to implement post-roast sorting, in 2016, was Counter Culture in Durham, North Carolina. Counter Culture employs two different sorting machines: a Bühler Sortex و Satake FMS2000. In this post we speak to Kyle Tush, Coffee Buyer and Quality Analyst at Counter Culture, who explains how they came up with the idea to start using the technology in their roastery.

More widespread adoption of post-roast sorting in specialty coffee came with the development of Sovda’s Pearl Mini — a colour sorter designed specifically for use in small scale roasteries, at a relatively accessible price. We also speak to Paul Stephens, head roaster at Rosso Coffee Roasters in Calgary, Alberta and Alexander Lipphardt, founder of Leuchtfeuer Coffee in Hamburg, Germany to find out more about how installing the Pearl Mini has improved their coffee.

The Optical Sorter

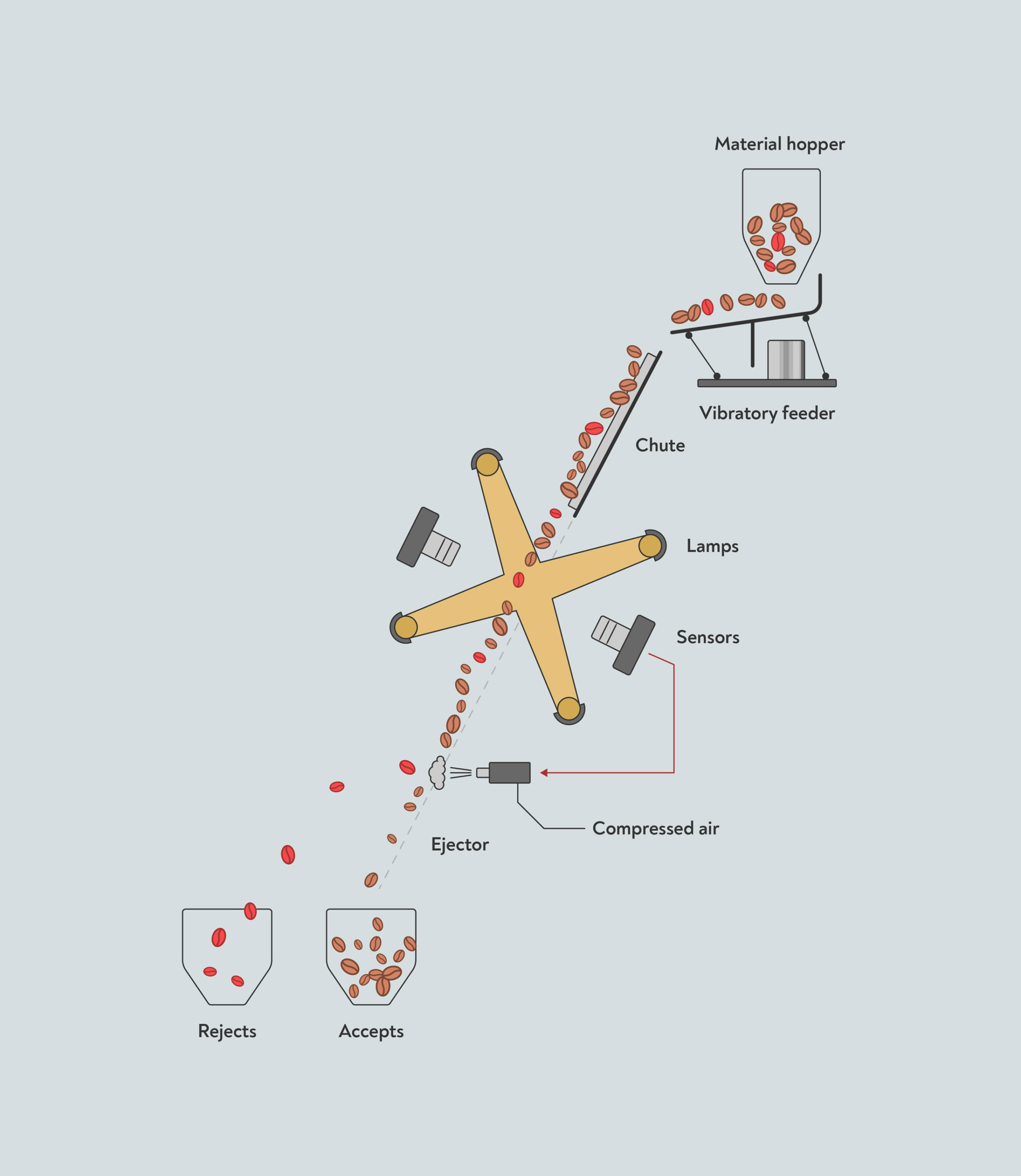

The sorting machines in question are called optical sorters. The optical sorter passes each bean in front of a camera, and removes any that don’t have the right appearance. The simplest optical sorters simply remove any beans that are the wrong colour, but more advanced machines also assess the shape of each bean, and detect frequencies of light well beyond the visible spectrum.

How an optical sorter works. A stream of beans passes in front of a sensor that detects the colour and shape of each bean. A puff of compressed air blows any beans that don’t meet requirements into a separate container.

How an optical sorter works. A stream of beans passes in front of a sensor that detects the colour and shape of each bean. A puff of compressed air blows any beans that don’t meet requirements into a separate container.

The first colour sorters were developed by the Electric Sorting Machine Company (ESM) in Michigan in the 1930s, and the technology was being applied to green coffee by the 1940s. ESM went on to be bought by Satake, who still make sorting machines today.

Optical sorters used in modern dry mills can easily remove any immature, discoloured, sour, or insect damaged beans that remain after processing. However, as our Brewers’ Cup competitors can tell you, there are still defects to be found in roasted coffee. Some of these defects might be caused during roasting — for example, a bean might get stuck in the roaster and be roasted twice. On the other hand, some beans might look perfectly fine when they are green, but turn out to be unusually pale after roasting — these are known as quakers.

All About Quakers

Quakers are pale after roasting because they are missing some of the sugars needed for the Maillard reactions to take place. Without the Maillard reactions, the beans don’t turn brown and don’t develop the typical aromas of coffee.

Quakers have a distinctive peanut shell, or straw-like aroma. Coffee made from quakers lacks sweetness, حموضة, and body, and can be highly astringent. Seven quakers in a cup is enough to have a significant impact on the coffee’s cup score (Rabelo et al 2021), but the SCA states that specialty coffee should not contain any visible quakers in a 100g sample.

Quakers stand out after roasting due to their pale colour, but can’t always be detected in the green beans.

Quakers stand out after roasting due to their pale colour, but can’t always be detected in the green beans.

Quakers were long thought to be the result of picking unripe fruit, when the seeds haven’t had time to fully mature. Immature seeds have a distinct, curled shape and can sometimes be picked out by sorters before the coffee is exported. However, insufficient nutrients or plant diseases can prevent the seed from fully developing, even if the fruit appears perfectly ripe on picking.

Discovering this fact was one of the main reasons that Counter Culture first decided to install colour sorters for their roasted coffee, explains Kyle Tush. “The decision to implement this … sprang out of the coffee leaf rust crisis,” he says. “We were noticing a higher number of quakers in lots purchased from longtime suppliers, whose standards for cherry selection were really high. We did a few small experiments with lots that were 100% perfectly red cherry when picked, yet once the coffee was in roasted form we were still finding quakers.”

The leaf rust epidemic made it clear that poor plant health could cause quakers to develop, even if the cherry was picked when it appeared perfectly ripe, Kyle explains — and there was very little that farmers could do about it. “Buyers such as ourselves are always asking for more from producers in regards to quality, but what were we doing on our end?”

The answer to that question was a colour sorter. Tim Hill, Counter Culture’s former head of purchasing, persuaded the company to install the Bühler Sortex in the Durham roastery in 2016, followed by the Satake FMS2000 in Counter Culture’s West Coast facility in early 2017.

The Bühler Sortex compact optical sorter at Counter Culture Coffee

The Bühler Sortex compact optical sorter at Counter Culture Coffee

The Benefits of Sorting

Even the best coffees contain quakers, explains Paul Stephens from Rosso Coffee Roasters. “The majority of the rejects are quakers so they have a woody, peanut flavour and are sometimes musty, even in 90 point coffees.”

As well as quakers, the optical sorters can remove other defects such as bits of cascara, or burned beans. “We have had stones, corn, metal, wood…you name it,” says Leuchtfeuer Coffee’s Alexander Lipphardt.

Sorting makes the coffee taste cleaner and more vibrant, Alexander says. Paul agrees, saying: “The unsorted coffees are less consistent and usually a bit more muted … with occasional harsh, burnt flavours.”

It’s extremely difficult to quantify the difference the sorting process makes in terms of the cup score, Kyle says. “On the other hand, when you taste the rejects it’s a very stark contrast between what gets removed and the rest of the ‘good’ coffee,” he says. “A lot of the cupping notes we get … are terms like burnt popcorn, hay, hollow, or peanut shells.”

Adding sorting steps at the roastery can also make it possible to get good results from coffee that would otherwise have to be rejected. Rosso Coffee Roasters use two Pearl Minis, one for green coffee, and one for roasted, which allows them to reprocess coffee to the standard they want. “Having the sorters allows us to purchase coffee from farmers that we have long term relationships with in years when their quality is lower and also when a coffee has a lower quality than expected,” Paul says.

Paul Stephens loading coffee into a Pearl Mini at Rosso Coffee Roasters

Paul Stephens loading coffee into a Pearl Mini at Rosso Coffee Roasters

Counter Culture have also found that the sorting machines widen the range of coffees they can use. “Having this capacity did allow us to use coffee we otherwise might not have been able to,” Kyle says. “We experimented with ‘C’ grades in Kenya and Papua New Guinea. We’ve found that there is some really great coffee in these less popular grades and sorting at higher loss percentages can clean them up quite a bit.”

Needless to say, the sorting machines do not eliminate the need for good processing at origin. “The Pearl Mini clearly does not magically turn a mediocre 80 point coffee into a competition lot that can be used at the WBC,” Alexander warns. “If a coffee has a lot of defects…I would rather save the money [on sorting] and buy better green coffee in the first place.”

Depending on the coffee and the number of sorting steps, the machines might reject anywhere between 1 and 5 percent of the coffee. The rejected beans are mostly used for seasoning grinders, or thrown on the compost heap — but at Counter Culture, they collect the rejected beans and re-roast them to a darker roast level, to be donated to local charities. “Tasting the re-roasted coffee is super interesting and not quite as abhorrent as one might think,” Kyle says. “It reminds me of really low quality grocery store coffee — though much fresher, of course!”

Invisible defects

As well as being faster and more cost-effective than sorting by hand, optical sorters can pick out defects that are hard to spot, or even invisible to the human eye. Subtle differences in colour can indicate uneven drying, for example, that would not necessarily be considered a defect. A preliminary experiment outlined in STiR magazine suggested that sorting green beans by the precise hue of green could bring out different flavours within the same lot.

Whether at the roastery, or the dry mill, optical sorters could even be used to measure the moisture level of coffee on a bean by bean basis. Water جزيئات strongly absorb certain frequencies of infra-red light, so an optical sorter equipped with the right detector could assess the moisture content of individual beans, or even determine how evenly distributed the moisture is within a single bean (Caporaso et al 2019). A similar technique could also be used to measure the fat content in individual beans, which could be used, for example, to detect any robusta beans that found their way into an arabica lot.

Optical sorters clearly have a lot of unrealised potential to improve the quality of the coffee we drink. As the technology continues to develop, and sorting machines become cheaper and more compact, colour sorting may become standard practice in coffee roasteries. The days of picking quakers out of a tray of beans may be numbered.

GOOD*

:)

Amazing good 👍