To prepare coffee beans for market, they are first sent to a dry mill to be hulled and then graded by size and density. This process removes the parchment, but in order to protect the green beans, millers do not remove the thin, papery layer — called silverskin — that is closely attached to the surface of the beans. During roasting, the beans expand and rub against one another in the drum. The silverskin loses contact with the beans and is blown out through the roaster’s exhaust. Roasters refer to this spent material as chaff, and they need to carefully manage its disposal.

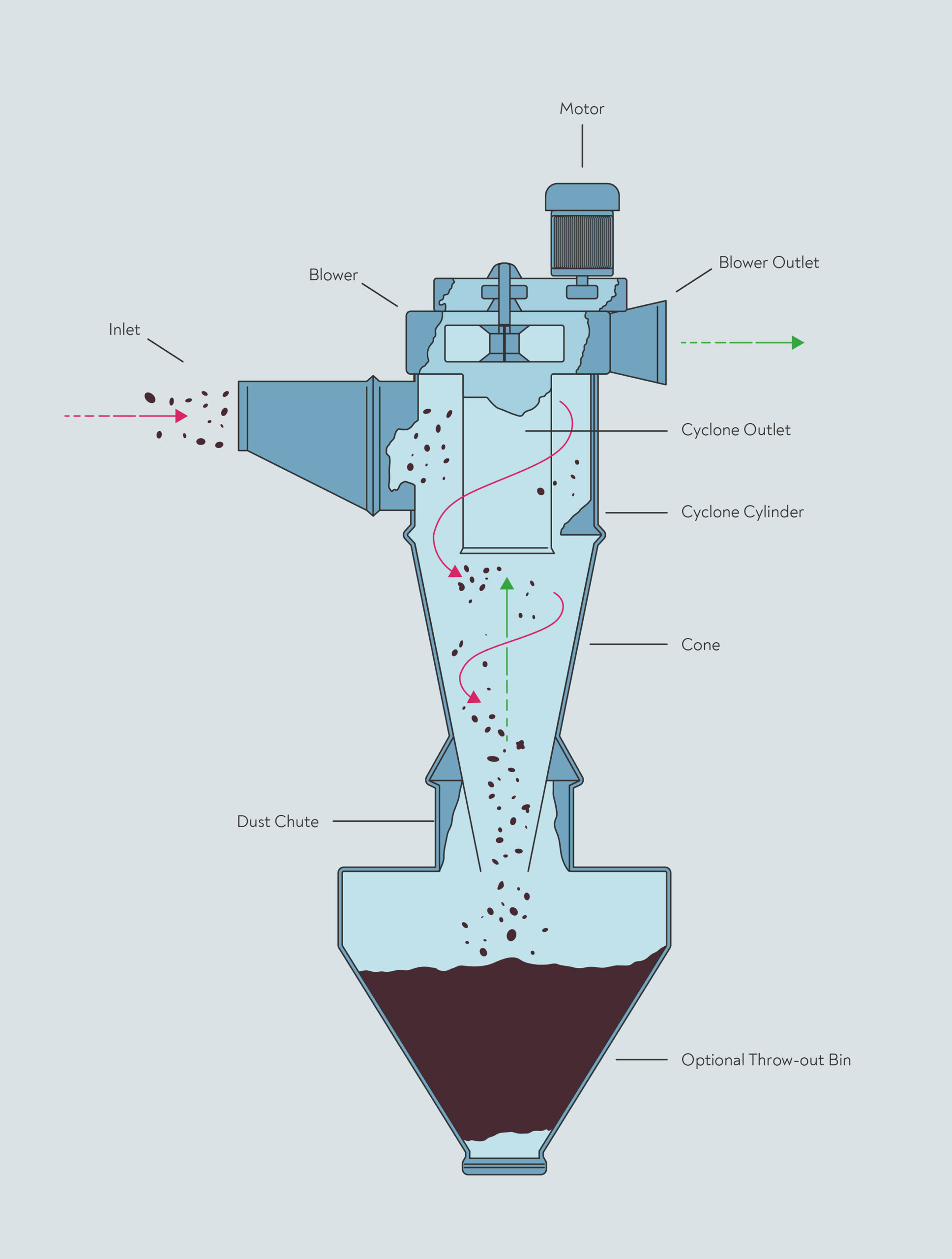

Virtually all commercial roasting machines have a cyclone designed to act as a chaff collector. Cyclones use centrifugal force to separate solids from a spinning column of air. They can remove 96% to 99% of the chaff and larger solid particles from exhaust gases (Fernandes 2019). The small fraction that is not captured in the cyclone goes up the flue. If the flue is not well maintained, the chaff can adhere to its walls, which over time can become sticky with creosote.

تدخل القشور إلى جهاز الفرز الدوّامي عبر المدخل وتدور حول حواف جدارنه. ويتم تثبيت أنبوب مخرج الجهاز أسفل النقطة التي يدخل فيها المدخل، مما يخلق نظام ضغط منخفض في الجزء السفلي من الجهاز وفي مجرى الغبار. يعمل فرق الضغط هذا على خفض القشور مع السماح للهواء النظيف بالهروب من خلال منفذ المنفاخ.

تدخل القشور إلى جهاز الفرز الدوّامي عبر المدخل وتدور حول حواف جدارنه. ويتم تثبيت أنبوب مخرج الجهاز أسفل النقطة التي يدخل فيها المدخل، مما يخلق نظام ضغط منخفض في الجزء السفلي من الجهاز وفي مجرى الغبار. يعمل فرق الضغط هذا على خفض القشور مع السماح للهواء النظيف بالهروب من خلال منفذ المنفاخ.

الوقاية من الحرائق

Both creosote and chaff are highly flammable, and creosote produces temperatures of over 1,000°C (1,800°F) when it burns — that’s hot enough to melt metal flue liners (CSIA 2022). The buildup of chaff and creosote in a roaster flue also has the effect of narrowing the space through which the air can escape. To avoid reductions in airflow, it is necessary for roasteries to establish and maintain a regular cleaning schedule.